2013 February

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Lenten Evening Oratory

Brompton Road, SW7 2RP

Lent 2013

Evening Oratory

with the Fathers

in the tradition of St. Philip Neri

WEDNESDAYS at 6.30pm

20.Feb.2013 – Little Oratory

The Oratory Choir

The Three Lenten Tasks: tasks for all the year

27.Feb.2013 – Little Oratory

London Oratory School Schola

Adversaries of the Spiritual Life: The Flesh, The World, The Devil

6.Mar.2013 – Little Oratory

The Oratory Choir

Our Lord speaks to His followers before the Passion

13.Mar.2013 – The Church

Holy Hour during 40 Hours Exposition (Quarant’Ore)

20.Mar.2013 – Little Oratory

Oratory Junior Choir

Our Lady’s Dolours (texts from Stabat Mater)

27.Mar.2013 – The Church

Tenebrae in Cena Domini

Vigil of Prayer at the Oratory

until

Friday 1 March 7am

There will be an Adoration Vigil (Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament) in the Little Oratory praying for the Church as we end the pontificate of Pope Benedict XVI, thanking God for all the graces during this pontificate and asking the guidance of the Holy Spirit for the cardinals as they meet to elect the new Pope.

The Vigil will begin Thursday 28 February at 9.30 in the evening and conclude with Mass at 7am the following morning.

Brompton Oratory

Brompton Road

London

SW7 2RP

Squabbles Over Szekler Flag

In Transylvania, a “flag war” has broken out between Romanian politicians and the representatives of the Hungarian-speaking Szekler people. As România Libera reports, no one is offended by flying the old Hapsburg flag over the fortress of Alba Iulia (De: Karlsburg, Hu: Gyulafehérvár), the Romanian government takes umbrage at the appearance of the blue-and-gold flag of the Szekler (or Székely) people who live primarily in three of Transylvania’s counties. (more…)

London Lately

From a Pimlico rooftop, Friday afternoon.

At lunch, Friday.

A Saturday Mass in St Wilfrid’s Chapel, the Oratory.

A surprisingly sunny afternoon, yesterday in Ennismore Gardens.

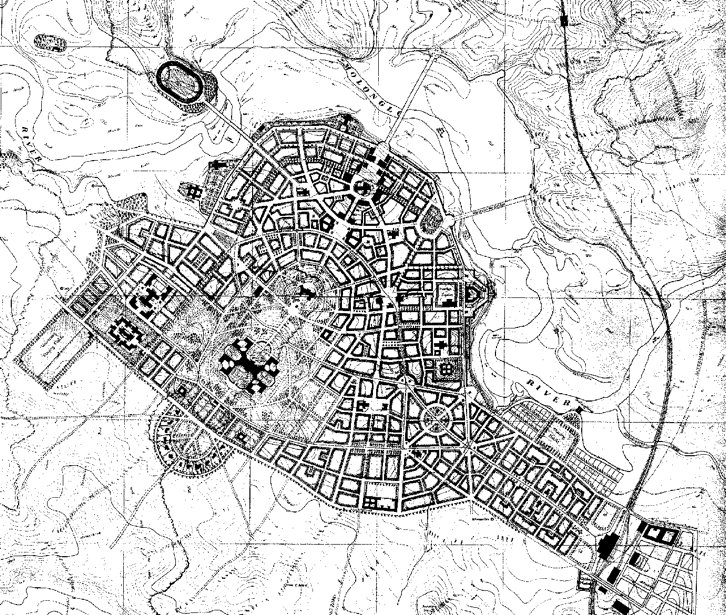

The most beautiful city never built

Ernest Gimson’s Canberra

Whenever I’m in in Westminster Cathedral, I feel obliged to nip in to and say a prayer in the chapel dedicated to St Andrew. The apostle is my patron many times over: in addition to being my name-saint, he is the patron of the university, the town, and the country in which I spent four luxurious years. His is one of the most finely decorated chapels in the cathedral, and boasts a beautiful mosaic depiction of the ‘Auld Grey Toun’ above the arms of the donor, the 4th Marquess of Bute. (His father, the eccentric 3rd Marquess, had been Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews.)

Stumbling upon the genial Cathedral Historian, Patrick Rogers, the other day, he shared with me that the stalls and kneelers in St Andrew’s Chapel are widely considered the finest works of arts-and-crafts furniture design in all of Great Britain. They are the creation of a man I had never heard of: the craftsman, designer, and architect Ernest Gimson.

An unfamiliar name is always a potential new avenue of knowledge down which to saunter, and so it proved with Ernest Gimson. His talent at furniture is undoubted but, given my obsession with architecture, it was instead that field of his expertise which particularly drew me in. It was then that I discovered his submission for the 1911-1912 Australian Federal Capital Competition.

The British colonies in Australia federated in 1901, and the dispute between Sydney and Melbourne as to which would be the capital of the youthful nation was settled by agreeing to build a new planned city within New South Wales (the state Sydney is in) but not more than 200 miles from Melbourne.

Ten years later, an international competition was announced to determine the design for this new capital being created ex nihilo on the banks of the Molonglo river, which was given the name of Canberra.

Of the 137 entries received, many of them were very handsome, but some of them were frankly awful. Rather than have a team of architects, artists, or urbanists choose the winning design, the Minister for Home Affairs, Mr King O’Malley, was the sole decision-maker.

He eventually chose the plan submitted by the Chicago architect Walter Burley Griffin, awarding a second prize to Eliel Saarinen of Finland, with third prize going to Alfred Agache of Paris.

The design I would have chosen, however, was Ernest Gimson’s.

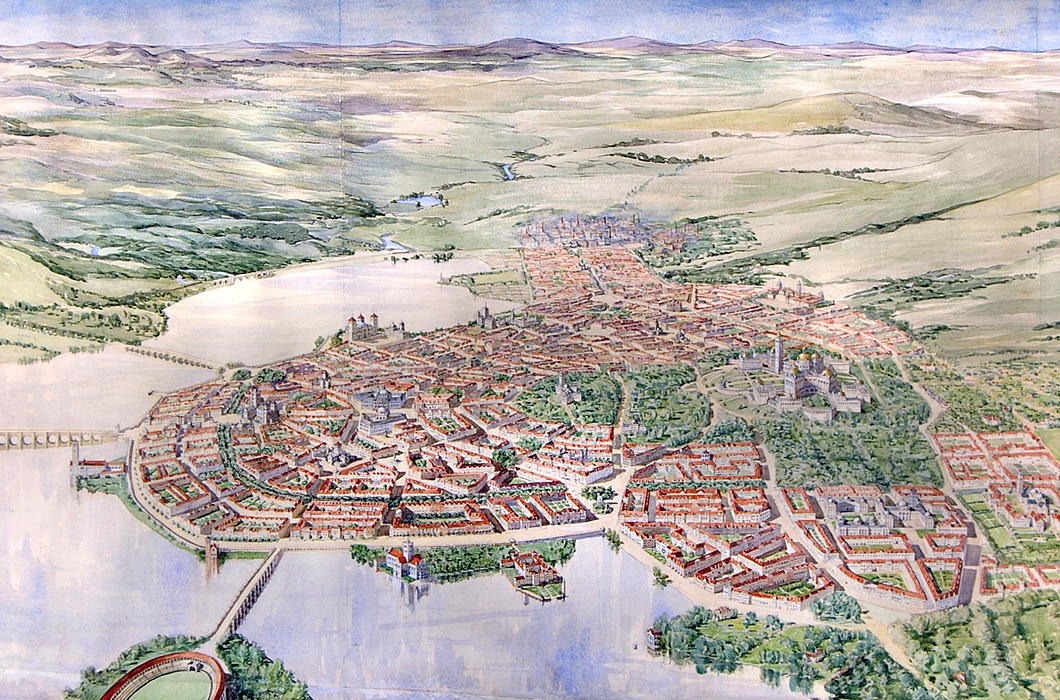

Gimson designed a compact capital city of 25,000 inhabitants that would be able to support itself based on neighbouring farms and small-scale industry.

The city is entirely concentrated along the south bank of an artificial lake and centred on a wooded park containing Kurrajong Hill and Camp Hill, with the streets of the city radiating down from there toward the lakeside.

Kurrajong Hill, with its dominating position over the city, was selected for the Houses of Parliament, with eight departmental buildings surrounding it on a lower terrace.

Official residences for the Governor-General and Prime Minister are located nearby, each with six acres of private grounds.

The State Hall is located atop the adjacent, slightly lower, Camp Hill, with the Printing Office and Mint located at either side, where the park ends.

North-west of Kurrajong is the City Hall, flanked by the Courts of Justice, with its main entrance facing towards the central park.

On a small hill nearby is the University, its double-domed central block surrounded again by ancillary buildings on a lower terrace. Playing fields are allotted nearby.

The market is located on the east side “with a covered arcade for the stalls enclosing an open square”, alongside a market house and technical colleges.

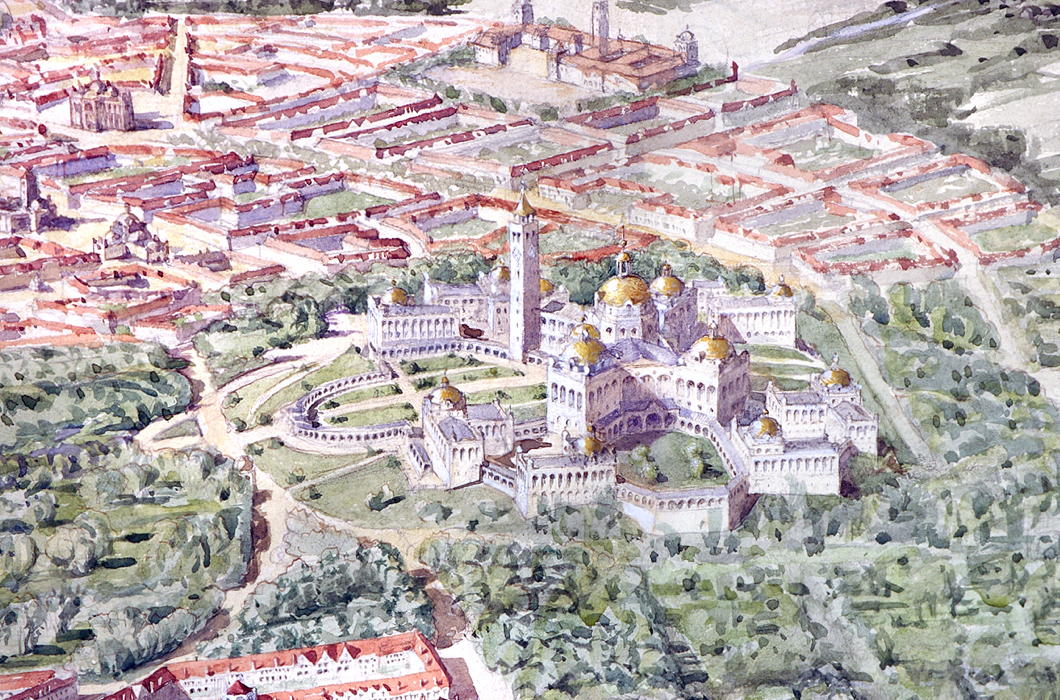

The Cathedral rises from the center of the city proper and forms an axis with the State Hall on Camp Hill and the Houses of Parliament atop Kurrajong.

At the near-midpoint of the street connecting the Cathedral to the State Hall, a public square is flanked by a National Art Gallery and Library. Around the Cathedral itself are the National Theatre and the General Post Office.

A stadium is located on the north side of the lake, connected to the city by a bridge, and further provision is made for siting barracks, gas works, a power station, cattle market, and other necessities.

Buildings would chiefly be faced in a light-coloured local stone which gives the plan, deeply influenced by tradition, both a brightness and a more vernacular feel.

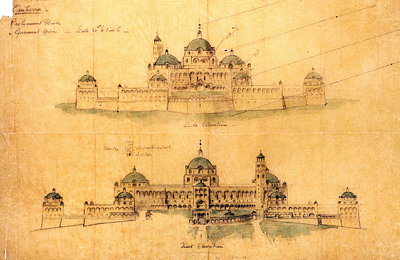

To discuss the design of the buildings is tricky: this proposal is an initial plan and, had it been selected, the architect would have had more time to then further refine what he was proposing.

The Houses of Parliament, with their eccentric X-footprint, are a curious conglomeration and not quite right. There seem to be a surfeit of towers that look too similar to one other.

But the Cathedral — my favourite part of Gimson’s plan — is a magnificent creation with an assertive central crossing tower that doubtless would become the visual focus of the city.

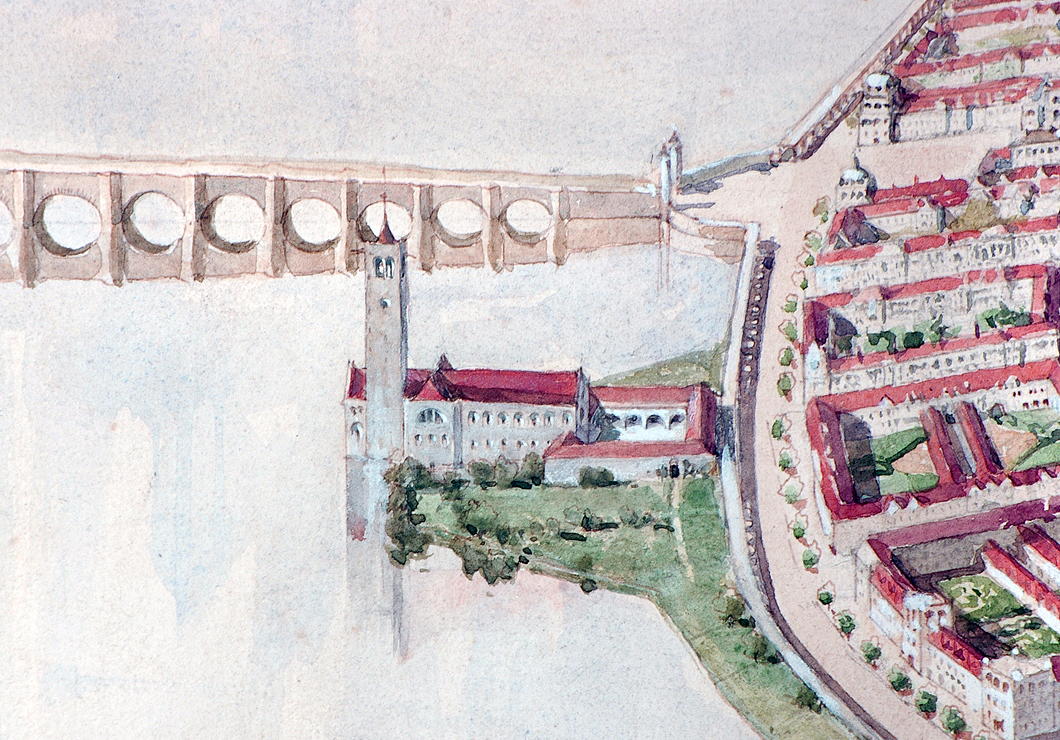

The embankment, with its long, generous, 20-foot-deep arcade providing “sheltered walk in hot and wet weather”, is both picturesque and useful.

“While screening in some measure the near part of the lake from the ground floor windows of the houses opposite,” the arcade, Gimson notes, “would enhance rather than diminish, the interest of the wider views.”

Indeed, it provides a useful transition point from lakeside to the rise of the buildings.

The architect’s layout of streets, public spaces, and important buildings, meanwhile, shows the influence of the aesthetic principles of the Austrian urbanist Camillo Sitte, now unjustly neglected since being contemptuously derided by Le Corbusier and other leading modernists.

Gimson’s Canberra is an unpretentious city: its lack of grandeur is what most likely secured its rejection by the fathers of the young and vigorous nation, who were keen to impress. Burley Griffin provided them with a plan redolent of modernity and progress, but marred by fading modishness.

The Gimson plan would have provided Australia a beautiful modern capital city with a design deeply rooted in tradition, and with appropriate consideration of locality and climate. One can imagine that, as the course of history continued, ‘Old Canberra’ would have formed a handsome and much-loved heart of an ever-growing city.

The humane, natural traditionalism of Gimson’s Canberra would have made it much more popular with ordinary people than the sprawling, overly spacious modern city that Canberra is today. Still, it provides a model that urbanists of the future should be mindful of and take inspiration from.

Protestant King in His Catholic Realm

George VI in Quebec

In the midst of some unrelated research the other day, I came across these photos of George VI on his first visit to Quebec as King in 1939. I think the Parlement du Québec is probably the only Commonwealth legislature to have a crucifix in its plenary chamber (c.f. ‘Christ at the heart of Quebec’, 25 May 2008). No, no, of course the Maltese do as well, in their surprisingly ugly parliament chamber. But Malta is now an island republic, while Quebec retains its monarchy.

In the above picture, the King and Queen of Canada hear a loyal address in the Salle du Conseil législatif of the Hôtel du Parlement in the city of Quebec. Below, the King speaks at a state dinner in the Chateau Frontenac. Seated is Cardinal Villeneuve, the Primat du Canada and Archbishop of Quebec.

A Rainy Day in Winchester

IT WAS LATE summer, neither particularly warm nor cold, and a bit rainy. I hadn’t seen Nicholas in a while but he wasn’t particularly keen on travelling into London. “Why not meet in Winchester?” he suggested, and, never having been to England’s former capital, I thought it was a good idea. I popped on the tube to Waterloo, got on a train, and in no time at all was in the county town of Hampshire. It’s a humanely size town, admirably located, and most famous for its medieval cathedral.

The thieving Protestants, not content with stealing all the cathedrals we built throughout the width and breadth of the land, highten the insult by charging admission to these former shrines and places of worship. I had arranged to meet Nicholas in the Cathedral, though, and the blighters got a good £6.50 out of me. I had a good wander round, though.

These mortuary chests contain the remains of the Saxon royalty of the kingdom of Wessex and later England.

Norman architecture is woefully underappreciated, and might form a useful style to return to today given its relative simplicity. So much Norman architecture was destroyed and replaced by Gothic during later periods of medieval prosperity, but at Winchester the Norman transepts remain.

William of Waynflete, buried here, was a high-flyer in his day. He was, varyingly, Bishop of Winchester, Headmaster of Winchester College, Provost of Eton, Lord Chancellor of England, and founded Magdalen College, Oxford. Not a bad innings.

Richard Foxe chose a more macabre memorial, but enjoyed similar success in this world: he was Bishop of Exeter, then of Bath & Wells, then of Durham, and finally of Winchester. He was Lord Privy Seal and founded Corpus Christi College at Oxford. Foxe and Erasmus sometimes wrote to eachother, and his elaborate crozier is on display at the Ashmolean.

The tomb of Henry Cardinal Beaufort is my favourite memorial in the cathedral. Beaufort — a Plantagenet — was Dean of Wells, Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Bishop of Lincoln, Lord Chancellor of England, and finally Cardinal Bishop of Winchester. He was a sometime papal legate for Germany, Hungary, and Bohemia, and most famously presided over the trial of St Joan of Arc.

One of the walls was inscribed with graffiti.

The cathedral is also the final resting place for the earthly remains of Hampshire native Jane Austen, but nevermind that.

Tours of the College were available, but we decided to leave it for another visit, and went on a wander in the direction of the Hospital of St Cross.

The Hospital of St Cross and Almshouse of Noble Poverty is the oldest charitable institution in England and the largest medieval almshouse. The church could be a small cathedral in and of itself, but as we arrived an interment was taking place, so we thought it best that it, too, was left for another day.

The Vigil for Life

25,000 March in Dublin to Protect the Right to Life

A bit late in the day to report on it, but the Vigil for Life in Dublin a fortnight ago was by all accounts a success. The Fine Gael/Labour coalition government has recently announced plans to liberalise Ireland’s strict protection on the right to life. Gardaí estimate that 25,000 people gathered on the southern side of Merrion Square, which leads on to Leinster House, the seat of the Oireachtas (Ireland’s parliament). Pro-abortion demonstrators staged a counter-demonstration nearby which drew 200 protesters.

The demonstration was organised by a variety of anti-abortion groups in Ireland, including Youth Defence and the Pro Life Campaign. Among those who spoke to the assembled was Tyrone GAA manager Mickey Harte (whose daughter Michaela was murdered in Mauritius in 2011).

“Ireland is almost unique in the Western world in looking out for, and fully protecting, two patients during a pregnancy — a mother and her unborn child,” Mr Harte said.

“We are here to oppose the unjust targeting of even one unborn child’s life in circumstances that have nothing to do with genuine life-saving medical interventions.” (more…)

A Bill Committee in the Commons

A Bill Committee meeting in one of the richly decorated committee rooms of the Palace of Westminster. The Minister is standing, rattling on in an explanatory defence of his government’s bill. Ostensibly these committees exist so that MPs can examine legislation in line-by-line detail and raise questions about whatever points or aspects they believe might cause problems if enacted.

“The question is that Clause 15 stands as part of the Bill.”

The Chairman, an MP of considerable experience, presides, assisted by a retinue of civil servants. He chews a pen and stokes his brow, frustrated by the boredom of the subject at hand. He is perhaps thinking of the weekend and the extreme unlikeliness that he will get down to the coast, and his sailboat, given the inclement weather.

A Scottish Member rises on a Point and the Minister yields the floor. Concerns are expressed about the precise meaning of Subclause 36 Paragraph C and insinuations made about potential costs. The Minister rises and suggests the Member’s criticism is excessively harsh. He then concedes he may have been imprecise in his explanation of the process involved in Subclause 36 Paragraph C.

The Doorkeeper, absurdly and arcanely attired in white tie, tails, and with the royal arms hanging from a gold chain round his neck, wears thick-rimmed glasses and leans back on a desk in a carefree fashion, blissfully paying little attention to the point the Hon. Gentleman has made in response to the proposed amendment.

“Just for the sake of clarity, we are not now talking about Amendment 13?”

“I have no intention of moving Amendment 13.”

“On a Point of Order then, Mr Chair, is it proper that the Member discuss Amendments 21 and 26 when he is not moving Amendment 13, which is the first Amendment to be considered?”

The Chairman corrects that it is perfectly alright for the Member to discuss whichever amendment he would like.

There are at least eleven civil servants in the room. One on the side hands a paper to another. He reads it and nods approvingly before passing it on to the civil servant next to the Chair. Another Member rises to discuss Amendment 54 Clause C.

“There’s an important role for an independent body to exercise scrutiny over this area and it would be wise for it to have a statutory basis.”

The entire proceedings are overshadowed by the continual sound of shuffling papers. One Member doodles on the day’s order-paper. A journalist leaves. The Member stops doodling and consults his iPhone. Then the Minister is grateful for that point. He is surprised but aware, since he was given this junior ministerial role, by the frequency with which this matter has arisen and has spoken before the relevant Select Committee.

Another Member’s face is illuminated by the glow of the iPad he is leaning over.

“Now before I become too Churchillian,” the Minister continues, “I think we’d better turn to the matter of the Amendments. Now the Honourable Member has, perhaps understandably, raised the point…”

A female Member smiles and shares a jest with one of her party colleagues. The Doorkeeper’s shift ends and he is replaced by one of his bearded confrères. The civil servant beside the Chairman folds a paper and stares unthinkingly into the distance.

“In respect for the Hon. Gentleman’s desire for continuing debate and discussion with the relevant authorities…”

“He hasn’t addressed my point about Subsection 2!”

The portly Doorkeeper moves with surprising adroitness in delivering a note from a Member to a civil servant across the room. The Minister’s PPS hands him a relevant paper. The Chairman smiles in response to one of the Minister’s light-hearted remarks.

“I’m sure the Minister will agree that this is not the beginning of the end but merely the end of the beginning.”

“If only!” a Member interjects.

It is 3:32pm. The MPs will be here for hours yet.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories