About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

‘I Have Prussiandom in my Blood’

Loriot on Prussia and Prussianness

November 2003

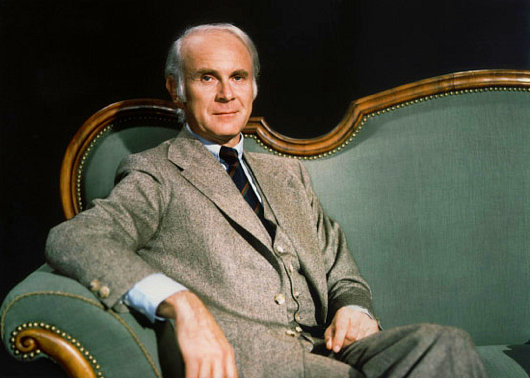

November 2003The Viennese weekly Falter interviewed Vicco von Bülow — better known as Loriot — in November of 2003. In part of the dialogue, Loriot explored the Prussianness of his family and upbringing, musing upon some aspects of what it is to be Prussian, turning away from the simplistic categorisations. Via Günter Kaindlstorfer.

…

Loriot: I am committed to my Prussian roots. I was born a Prussian, I have Prussian, so to speak, in my blood. That this defines you for yourself is not new. One is born there, so one has to accept it.

Prussian vices have caused too much harm over the past 150 years.

Loriot: That’s right, I will not deny it at all. Nevertheless, I am proud of my native town of Brandenburg; I am also proud of my country of origin. Here I will not deny, however, that I have been occasionally affected by the disaster that this country has done throughout history, time and again. Only: Which country has, over the centuries, not caused many evils? I will not have the Prussian reduced only to its negative sides.

Where do you see the positive side?

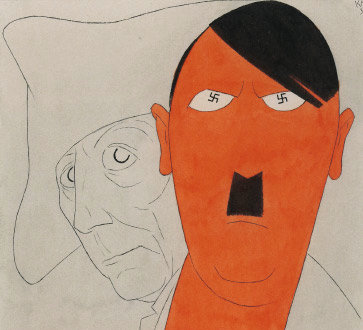

Loriot: There are also advanced aspects: Frederick the Great, for example, was the first to abolish serfdom and torture. These were big and bold reforms for its time. In addition, the Prussian State has developed an exemplary civil service. Against bribery and corruption, the Prussian officials were immune for centuries. Such a thing was not self-evident. So, the Prussian state was in some ways quite exemplary. But only now have the Prussians just gotten off the fence about war, and the legendary Prussian discipline made governance easier for the Nazis, one would have to say. If people in the Nazi era had been, attentive, critical, and aware, if they had been less obedient, then the world would have been spared much.

Loriot: There are also advanced aspects: Frederick the Great, for example, was the first to abolish serfdom and torture. These were big and bold reforms for its time. In addition, the Prussian State has developed an exemplary civil service. Against bribery and corruption, the Prussian officials were immune for centuries. Such a thing was not self-evident. So, the Prussian state was in some ways quite exemplary. But only now have the Prussians just gotten off the fence about war, and the legendary Prussian discipline made governance easier for the Nazis, one would have to say. If people in the Nazi era had been, attentive, critical, and aware, if they had been less obedient, then the world would have been spared much.

You can start with the soldierly virtues of the old Prussian something?

Loriot: I am, like everyone, influenced by my upbringing. My father came from an old Prussian military family. Prior to joining the private sector, he was a police officer. Such a thing certainly leaves some traces in the personality of a person.

What must be thought of your father? As a man who constantly banged his heels together?

Loriot: No, but he was undoubtedly a man of controlled and disciplined. One must keep his emotions under strict control he has drummed into me and my brother. I could not kiss him, for example. Men do not kiss, that was one of his maxims; he was adamant.

And your mother, you were allowed to kiss?

Loriot: My mother died when I was six years old. I grew up with my grandmother.

As you can see the character of your Father which is in retrospect?

Loriot: I’ve learned a lot from him about the vital importance of manners, for example. Through and through, he had a respectable appearance. As a virtue, self-control was central to my father. He never let himself go. I’ve rarely seen him without a tie. At the same time you could die laughing with him, he also had incredibly funny sides. However, it must be said: the time of militarism, which my father embodies in some ways — those days are over, thank God. The war doesn’t play in people’s minds the same role it once did in Germany.

Herr von Bulow, you represent your whole habitus produces the ideal type of conservative gentleman. Are you really a conservative man?

Loriot: Terms like “conservative” and “progressive” I try to avoid as a rule. Whether one likes it or not, these words are always politically connoted. I strictly keep out of party political matters.

How did you vote last time?

Loriot: One doesn’t tell.

You are a man of the center?

Loriot: Sometimes I sympathize with the political positions of a party, then again I like more the views of others. The truth is never on one side. Each direction has its positive aspects, which should be acknowledged.

I remember a Spiegel article, which must have been in the late 1980s. It said something like: “The West German intelligentsia is left-wing. Basically, there are only two right-leaning intellectuals in the country: Ernst Jünger and Loriot.”

Loriot: This can only be a joke.

It was actually printed.

Loriot: Me as “Rechtsintellektueller”? I can only laugh! So, in this attribute I fail to recognise myself yet again.

Loriot: Me as “Rechtsintellektueller”? I can only laugh! So, in this attribute I fail to recognise myself yet again.

Are you addicted to harmony?

Loriot: I am convinced that most conflicts can enclose in a considerate and atmosphere characterized by mutual respect. One mustn’t shout like a madman to enforce one’s point of view.

They seem very calm, very calm. Do you know something like stress?

Loriot: In order to have stress, I have too little time. It may, so far, just not have come, that I feel stressed. If one is stressed, you have done more than you can afford. This one must not allow.

Do you suffer from the aging process?

Loriot: Yes, certainly.

How do you handle it?

I rush myself less than before. In recent years, I have occasionally been an opera director, made a few drawings, and prepared a film; such a programme I now no longer have the audacity for. That mustn’t be. At my age it is safer to take things a little more quietly, don’t you think?

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Ernst Junger, I have to say, is an infinitely more important, impressive, and sympathetic figure than this mere comic, and not only because he converted to Catholicism a year before his death aged almost103.

I have no idea whether or not this man was a Rightist. Like most Germans today, he shows himself frightened to death by the very mention of such a possible thought crime. Junger never denied or apologised for his past – instead he learned from it.