About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

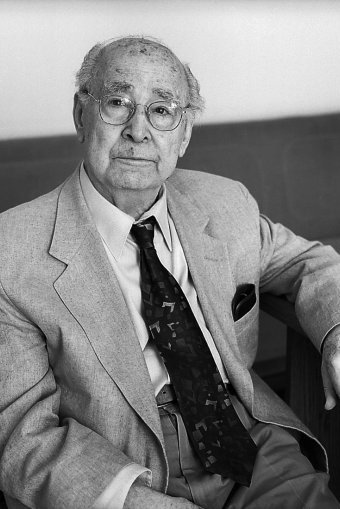

Thomas Molnar, 1921–2010

The Catholic philosopher and historian Thomas Molnar died last week in Virginia at eighty-nine years of age, just six days short of reaching his ninetieth year. Born Molnár Tamás in Budapest in 1921, the only son of Sandor and Aranka, Molnar was schooled across the Romanian border in the town of Nagyvárad (Rom.: Oradea) in the Körösvidék, a region often included in Transylvania and an integral part of Hungary until the Treaty of Trianon cleaved it a year before. In 1940 he moved to Belgium to begin his higher education in French, and as a leader in the Catholic student movement he was interned by the German occupiers and sent to Dachau. With the end of hostilities, he returned to Brussels before arriving home in Budapest to witness the gradual Communist takeover of Hungary.

and historian Thomas Molnar died last week in Virginia at eighty-nine years of age, just six days short of reaching his ninetieth year. Born Molnár Tamás in Budapest in 1921, the only son of Sandor and Aranka, Molnar was schooled across the Romanian border in the town of Nagyvárad (Rom.: Oradea) in the Körösvidék, a region often included in Transylvania and an integral part of Hungary until the Treaty of Trianon cleaved it a year before. In 1940 he moved to Belgium to begin his higher education in French, and as a leader in the Catholic student movement he was interned by the German occupiers and sent to Dachau. With the end of hostilities, he returned to Brussels before arriving home in Budapest to witness the gradual Communist takeover of Hungary.

Molnar left for the United States, where he earned his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1950. He frequently contributed to the pages of National Review after its foundation by William F. Buckley in 1955, and his periodic writings were often found in Monde et Vie, Commonweal, Modern Age, Triumph, and other journals. From 1957 to 1967 he taught French & World Literature at Brooklyn College before moving on to become Professor of European Intellectual History at Long Island University. In 1969 he was a visiting professor at Potchefstroom University in the Transvaal. In 1983 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Mendoza in Argentina while he was a guest professor at Yale. After the fall of the Communist regime in Hungary, he taught at the University of Budapest and at the Catholic University (PPKE). In 1995 he was elevated to the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

While his first book, Bernanos: his political thought and prophecy (1960), was well-received, it was Molnar’s second published work that was arguably his best known. The Decline of the Intellectual (1961) was, in Molnar’s own words, “greeted favorably by conservatives, with respectful puzzlement by the left, and was dismissed by the liberal progressives.” Gallimard began discussions to print a French translation as part of its prominent Idées series, before the publisher’s in-house Marxist Dionys Mascolo vetoed it for its treatment of Marxism as a utopian ideology. The celebrated & notorious Soviet spy Alger Hiss complimented it in a Village Voice review, but Molnar noted that The Decline of the Intellectual‘s harshest criticism came from liberal Catholic circles. “Obviously,” he wrote, “in that moment’s intellectual climate, they would have preferred a breathless outpouring of Teilhardian enthusiasm.”

The book argued, from a deeply conservative European mindset, that the rise of the intelligentsia during the nineteenth century was tied to its capacity as an agent of bourgeois social change. As the intellectual class increasingly shaped the more democratic, more egalitarian (indeed, more bourgeois) world around it, the intelligentsia’s vitality, so tied to its capability to enact social change (Molnar argued), became self-destructive. The “decline” set in as the intelligentsia searched for alternative methods of social redemption in increasingly extreme fashions (such as nationalism, socialism, communism, fascism, &c.) and led to the intellectuals allying themselves with ideology, which is the surest killer of genuine intellectual and philosophical speculation.

The same year Molnar’s The Future of Education was published with a foreword by Russell Kirk, whose study of American conservative thinkers, The Conservative Mind, was admired by Molnar. Among the many works that followed were Utopia, the perennial heresy (1967), The Counter-Revolution (1969), Nationalism in the Space Age (1971), L’éclipse du sacré : discours et réponses in 1986 with Alain Benoist, and the following year The Pagan Temptation refuting Benoist’s neo-paganism, The Church, Pilgrim of Centuries (1990), and in 1996 Archetypes of Thought and Return to Philosophy. From then until his death, the remainder of his new books have been published in his native Hungarian language.

Molnar and his work have become sadly neglected for the very reasons he detailed in his major work: the overwhelming triumph of ideology over the intellectual sphere. While Russell Kirk defined conservatism as the absence of ideology, modern conservatism in America has become almost completely enveloped by ideology, and the Molnar’s deep, traditional way of thinking — influenced to a certain extent by de Maistre and Maurras — is now met more by silence and ignorance than by direct condemnation.

The triumph of ideology (be it on the left or the right) was aided and abetted, Molnar argued, by a culture dominated by media and telecommunications. “Around 1960,” Professor Molnar wrote later in his life, “the power of the media was not yet what it is today.”

Hardly anybody suspected then that the media would soon become more than a new Ceasar, indeed a demiurge creating its own world, the events therein, the prefabricated comments, countercomments—and silence. … The more I saw of universities and campuses, publishers and journals, newspapers and television, the creation of public opinion, of policies and their outcome, the less I believed in the existence of the freedom of expression where this really mattered for the intellectual/professional establishment. For the time being, I saw more of it in Europe, anyway, than in America: over there, institutions still stood guard over certain freedoms and the conflict of ideas was genuine; over here the democratic consensus swept aside those who objected, and banalized their arguments. The difference became minimal in the course of decades.

Needless to say, the world of American conservatism has been silent in responding to the death of Professor Molnar.

Ideology’s enforced forgetfulness aside, Molnar’s native Hungary renewed its appreciation for him just before his death: last year the Sapientia theological college organised the first conference devoted to his works, which was well-attended and much commented-upon in the Hungarian press. Besides his serious corpus of works, Molnar is survived by his wife Ildiko, his son Eric, his stepson Dr. John Nestler, and his seven grandchildren.

Requiescat in pace.

Previously: Understanding the Revolution

Elsewhere: Professor Thomas Molnar, In Memoriam

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Ironically, I just recently ordered a received a couple of Dr. Molnar’s books (Africa: A Political Travelogue; and The Counter Revolution. I have a number of his other works but would like to eventually get most if not all the others (at least the ones available in English). He is certainly someone that present day “conservatives” would do well to study. May he rest in peace.

For what it’s worth, I purchased his book “Authority and its Enemies” many, many years ago from the Conservative Book Club. I re-joined the club a couple of years ago and have purchased a grand total of two books since (a couple of volumes of golf humor by P.G. Wodehouse). Mostly, the offerings are of Sean Hannity, Glenn Beck, and the like. Just one small example of the failure of the “conservative” movement and the need to re-discover giants like Dr. Thomas Molnar.

I note with disgust but no surprise that National Review Online has ignored this great thinker’s death.

I first realised that NR was no good when, many years ago, it published a viciously negative and blatantly Americanist review of his The Counter Revolution.

Rather like the bumptious imp at the Daily Telegraph who recently told us that de Maistre led straight to Hitler.

Dimwits the lot of them.

Professor Molnar’s reputation is high not only in Hungary, but to some extent also in Poland, Croatia, Latvia — that is in countries which experienced the extreme forms of leftish ideologies. Where such an experience is missing, most of the population, a good part of the intelligentsia included, just do not have the proper grasp of the matter. Yet it would be easy just to have a look at neighboring Cuba where all those totalitarian consequences have been realized. — The Thomas Molnar Legacy Project has been started by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and we have hope that it will lead to substantial results in the research and study of Dr. Molnar’s works and their intellectual ad historical connections.

I live in Richmond where he died and met him personally, he signed one of his books for me and i will always treasure it

A profound and eloquent sage, whose work I, for one, came to know via … National Review. (I speak of National Review in its great days, the days of Kirk, Sobran, Buchanan, Burnham, etc.) It would have been so easy for me to write Thomas Molnar a letter simply thanking him for all the fine articles and books that he produced, but, of course, one is never prompt enough in getting around to that task. And it’s too late now. RIP indeed.

Dr. Thomas S. Molnar from another perspective: As an eager and bedazzled college freshman at the San Francisco College for Women (1954-1958), I was awestruck by Dr. Molnar, who taught the humanities and some French classes there. To me he was the epitome of the European intellectual and I was definitely not in his league, although longed to be. I can still see him, heels clicking down the corridors, head slightly bent, briefcase in hand. He wore black horn-rimmed glasses and his dark hair was slightly balding. Not particularly beguiling, but there was definitely something very attractive about him. He must have chuckled inwardly at the flirtatious manifestations of this silly freshman. He was about larger things and soon moved on. Thinking about him years later after the post-Vatican II debacle, and the decline of the RSCJs, I wondered what his thoughts were. I see I have a lot of catching up to do. Jane Conrad Kosco, San Francisco College for Women Class of 1958.

I was sorry to read of the death of Thomas Molnar. While I have not read any of his books, I always read the articles he contributed to “National Review” magazine throughout the 1970’s. His gentlemanly manner always impressed me, as did his willingness to believe that even an opponent might have a better nature through which they might be appealed.

As an example of his generosity of spirit, I recall an article Professor Molnar wrote about Sartre that appeared in “National Review” sometime in 1980 after Sartre’s death. At that time, intellectual circles in France were astir because of a series of articles written by Benny Levy, a Jewish friend Sartre had made at the end of his life. Levy reported that Sartre had renounced his earlier conviction that “existence precedes essence”, and that–while not explicitly professing belief in the Christian God–Sartre had abandoned his doctrinaire atheism as well, and was moving towards faith.

Sartre’s reward for this was to denounced by his old friends and compatriots; Simone de Beauvoir included. But not by Molnar, who noted this change of heart, praised it, and allowed that grace may have finally touched the heart of someone who probably had never known it before.

If only we had more such as Thomas Molnar!

I was raised and trained in evangelical institutions, and then even taught in evangelical institutions. But as I explored political philosophy and got into politics myself, Thomas Molnar was a major influence. It was his writings, along with Kirk, Jaki, Novak, Maritain, and Dawson, that took me into the Catholic Church 18 years ago. I shall ever be grateful to Molnar for his writings and his faith.

I only just yesterday found out about his death while searching for any books of his I haven’t read. The world is at a loss for the loss of Thomas, but God and Thomas are rejoicing in heaven. Heaven will be a better place for me too when I can sit at the feet of both he and Jesus.

Sir,

This is rather late by two years, but in view of the comment of one Jane Kosco about Dr. Molnar that he taught French at the San Francisco College for Women—and her description—it’s apparent that all the Internet blurbs about him omitted the time he spent on the West Coast. Her description of him fits the photograph and my recollection of him. He was on the Pacific University (Forest Grove OR) faculty as a French professor in academic 1951-52 prior to his San Francisco stint. Rumors were that he was a political refugee and Pacific was a refuge for several other academics during the McCarthy era. I am stunned that we had no idea about his importance in philosophy and, late in his life, it would appear, his stellar reputation on the political scene. Next week is Homecoming at Pacific, and I am going to give him a shout-out. Who knew?

Barbara G. Ellis, Ph.D.,

principal

Ellis & Associates, LLC, Portland OR

Eric Molnar-the son of Thomas Molnar-has been wronged by the family of his father’s other wife. Eric is a friend of mine, and he has asked me to post these his words: “To the step children of Thomas Molnar: Being his only son by blood, I would like to settle the property in Paris, France to which I have rights. My father was not very generous to me, and this property is the only thing I have left of his. I feel that I am entitled to my legacy, and to close that part of my past so it will not linger on and on. “ Written March 17, 2015. Eric Molnar, New York, NY.

What was Dr. Molnar doing in Richmond at the time of his death?