About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

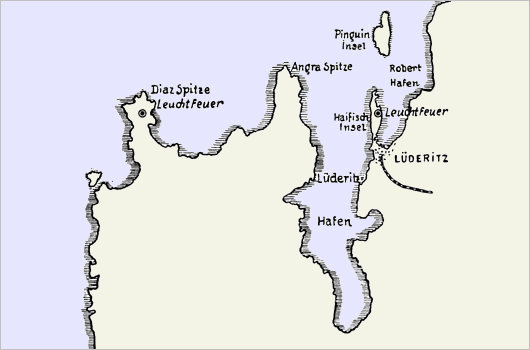

Diaz Point

You drive to the end of the world, turn left, and continue. That’s the way to get to Diaz Point. Namibia’s coastline is supposed to be the least hospitable on the planet, with desert meeting salty ocean with naught in between. Staying the night at Seeheim, an agglomeration of half a dozen houses nearby a stone castle hotel, we woke early and drove the 200+ miles west through the arid rocky desert. The experience is made all the more interesting for the 16,000-square-mile “Restricted Diamond Zone” one drives on the northern periphery of. Namibia’s diamonds are primarily alluvial deposits, meaning they rest on ancient river beds, sitting on the soil or resting just a few feet below. The forbidden territory’s guards are believed to have a policy of shooting first and asking questions later. There are over sixty countries in the world smaller than the Sperregebiet (forbidden area), as the Restricted Diamond Zone is colloquially known.

Eventually — passing through the area inhabited by the wild horses of the Namib, descendants of German cavalry horses and farm animals variously escaped or set free — you arrive at the town of Lüderitz on the Atlantic coast. Besides its German street names (Zeppelinstraße, not to mention Bismarck, Bahnhof, Moltke), the town’s architecture is a curious Teutonic colonial, reinvented for the almost-tropical locale. From one or two of the local businesses, one could easily imagine a slightly overweight German in a linen suit and panama hat, with an eye-patch as well as a cane for his limp, ordering around the natives crudely while engaged in some nefarious criminal enterprise or campaign of sabotage.

But for Diaz Point, you go to Lüderitz, turn left, and go further still. Driving south from the colonial town, you encounter a barren, rocky, and utterly colourless landscape, the grey tones of which immediately bring to mind the surface of the Moon. Am I still on Earth? Only the blue sky and the occasional appearance of vegetation remind you that you’re still on the third planet from the Sun.

Finally you see the water again. Arriving at Diaz Point, you go down a long wooden walkway to the rocky promontory that rises above the ground. The wind from the angry South Atlantic batters you about and tousles your hair in every direction. At the end of the wooden walk, you climb the stone steps and ascend to the top of the little promontory.

On the return journey from his 1487–1488 expedition around Africa, the Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias landed at the point that now bears his name and erected the Padrão de Santiago. (Dias’s name was often rendered with an ‘z’ rather than ‘s’, meaning this place is known as Diaz Point, Dias Point, Diaspunt, or Diazpunt). The padraos (or padrões) were small monumental crosses bearing the royal arms of Portugal, erected to legitimise Portugal’s territorial claims as well as to act as signs of thanksgiving to God for safe travels and in hope for the conversion of these un-Christian lands.

Dias erected padraos at Kwaaihoek near Port Elizabeth, his eastern-most landing point, at Buffelsbaai on the Cape Peninsula (not to be confused with the other Buffelsbaai), and here, east of Lüderitz. The remnants of the Kwaaihoek padrão were only discovered in the 1930s, were reassembled, and the relic is now displayed in the library at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. From the 1930s until the 500th anniversary of Dias’s 1488 journey around the Cape of Good Hope, the Lisbon Geographical Society funded the recreation of the African padraos in their original location. In addition to this, a replica of the Kwaaihoek padrão occupies a prominent place in the Market Square beside Port Elizabeth’s City Hall. These monuments stand as testimony to the first implantation of the seed of the Faith at the far end of Africa, years before Columbus reached the New World.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Utterly fascinating. The sort of thing which only Mr Cusack provides.

The Baron has said it. You’ve a rare quality; here displayed alone and unalloyed.

great article. Thank you. It brings back forty year old memories. I spent two months in Luderitz and its seaward viscinity in 1967 on board the SAS Haerlem, a South African Navy in-shore hydrographic survey ship. It was during the days of compulsory national service and I was one of its conscripted crew members. Luderitz was a fascinating place. I would have been quite glad to go ashore and stay there, fascination with its history aside, because the Atlantic off that part of Africa is uncompromisingly horrible. The entire crew used to be sick as dogs every time we were at sea. I remember two pubs in the town the crew used; one was Kapps and the other Rummlers. The officers frequented Rummlers and the ratings Kapps. As young fellows we seldom had to dip into our meagre savings despite the cheap beer – 20c a pint if I recall – because the locals were endlessly generous to us’seesoldaten’ in uniform. Of course, their largesse meant we suffered even more out on the briny than we would have had we eschewed their generous liquid hospitality.

Kapps is still there; don’t know about Rummlers. 20c a pint though — what a dream!

Yes, it does seem a dream these days. As a national service Able Seaman (2nd class)in 1967, we were paid the staggering amount of R15 per month, of which about R5 was deducted for messing fees and other sundries. A thirsty sailor could recklessly consume a lot of his monthly pay in one bibulous week at Kapps. But thanks to the open-handed generousity of those Suidwes Duits gentlemen, we hardly had to worry about our liquidity. In both senses of that lovely word.

Nice post, a friend of mine just forwarded because of the reference to Luderitz. theindiaroad.com describes the story of Dias’s journey, as well as that of Diogo Cão before him (he made it past the mouth of the Congo), and Gama’s subsequent expedition to Calicut in 1497.

In context, a friend of mine, Cmdr. Malhão Pereira, Portuguese navy ret., former commander of the Sagres cadet training vessel, was one of the specialists invited to analyse the wreckage of the Bom Jesus, which sank near the mouth of the Orange river, deep in de Beers country.

You can read about that on my blog (linked through the site above), but given here for convenience:

http://theindiaroad.wordpress.com/2009/10/01/into-africa/

or you can go straight to the article in National Geographic if you prefer:

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/10/shipwreck/smith-text

regards

Peter Wibaux