About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Some Afrikaners

“In my father’s shop,” writes the photographer David Goldblatt, “serving Afrikaners, I found, almost in spite of myself, that I liked many of them and, to my surprise, that I was beginning to enjoy the language. There was a warm straightforwardness and an earthiness in many of these people that was richly and idiomatically expressed in their speech. And, although I have never advanced beyond being able to speak a sort of kombuistaal, I delighted in our conversations. Yet, withal, I was very aware that not only were most of these people Nationalists, strong supporters of the Party and its policies, but that many were racist in their very blood. Although anti-Semitism was now seldom overt, they made no secret of their attitude to blacks, who at best were children in need of guidance and correction, at worst sub-human. I was much troubled by the contradictory feelings of liking, revulsion, and fear that these Afrikaner encounters aroused in me and felt the need somehow to come closer to these lives and to probe their meaning for me. I wanted to do this with the camera.

“I had begun to use the camera long before this in a socially conscious way. And so I began to explore working-class Afrikaner life in our district. I drove out to the kleinhoewes around the town. I would stop and ask people if I might do some portraits of them or spend time with them while they went about whatever they were doing. In this way I became intimate with some of the qualities of everyday Afrikaner life in these places, and with some of its deeply embedded contradictions.

“An old man sits for me. A black child comes and stands next to him, looking at me with curiosity. The man turns and says to the child, ‘Ja, wat maak jy hier, jou swart vuilgoed?‘ (Yes, what are you doing here, you black rubbish?), the insult meant and yet said with affection. How is this possible? I don’t know. But the contradiction was eloquent of much that I found in the relationship between rural and working-class Afrikaners and blacks: an often comfortable, affectionate, even physical intimacy seldom seen in the ‘liberal’ circles in which I moved, and yet, simultaneously, a deep contempt and fear of blacks. …

“Travelling through vast, sparsely populated parts of the country with my camera became a major part of my life at that time. I think that our landscape is an essential ingredient in any attempt at understanding not just the Afrikaner but all of us here. We have shaped the land and the land has shaped us. Often the land was unforgivingly harsh. Yet, the harsher the landscape the stronger the Afrikaners’ sense of belonging seemed to be. Many of the people whom I met in the course of those trips had a rootedness in the land of which I was very envious. Envious in the sense that I couldn’t claim 300 years of ancestry in this country. Yet, increasingly, I felt viscerally bonded to it.”

The son of an ostrich farmer waits with a labourer for the day’s work to begin, near Oudtshoorn, Cape Province, January 1967.

J.G. Loots of the farm Quaggasfontein where his family had farmed for more than 200 years. There were several prize ewes. He called each in turn by name, and each came to be petted, Graaff-Reinet, Cape Province, December 1966.

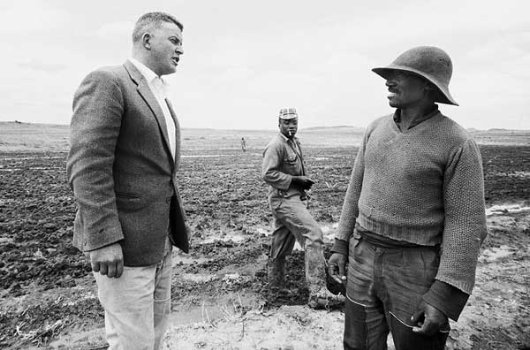

Johannes van der Linde, farmer and major in the local army reserve, with his head labourer ‘Ou Sam’. In the manner of respectful indirect address used in Afrikaans as between a parent and child, van der Linde asked, ‘Old Sam, does the Baas swear at you?’ To which the reply was, ‘No Baas, the Baas does not swear at me.’ Near Bloemfontein, Orange Free State, 1965.

A protea grower and his family on their smallholding near Groot Drakenstein. They were uncertain of how long they would be able to continue there, for they feared removal under the Group Areas Act, near Paarl, Cape Province, 1965.

[The Group Areas Act forcibly removed whites from areas the government had designated as non-white, and vice versa.]

Making a coffin for the body of a neighbour’s servant whose family could not afford to buy one, Bootha Plots, Randfontein, Transvaal, 1962.

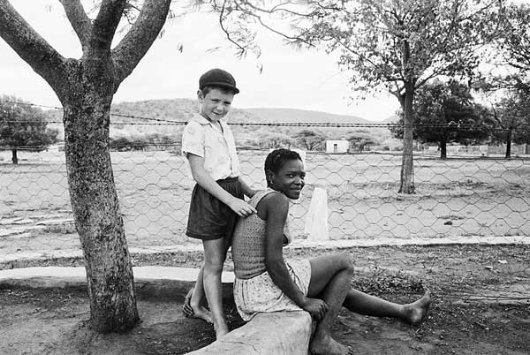

The farmer’s son with his nursemaid, on the farm Heimweeberg, near Nietverdiend in the Marico Bushveld, Transvaal, 1964.

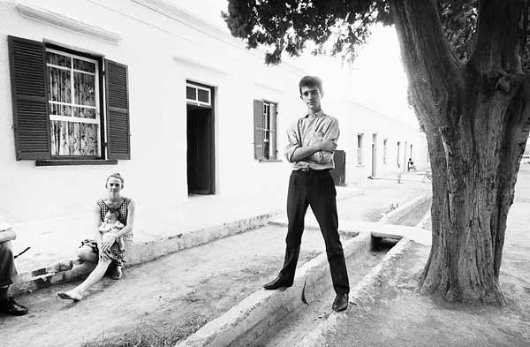

A clerk and his family in front of their house in Graaff-Reinet. He hoped to win a competition so that he might study medicine, Cape Province, 1966.

4 p.m. at a traffic light in Pretoria. This, the administrative capital of the country, was a city of Afrikaner civil servants, Transvaal, 1967.

The commando of National Party supporters that escorted Dr Hendrik Verwoerd to the party’s fiftieth anniversary celebrations, De Wildt, Transvaal, October 1964.

[The middle horseman in the front rank is Leon Wessels, who later became Deputy Minister of Law and Order in the National Party government. He was also the first senior member of that party to apologise for apartheid.]

The farmer’s wife. Near Fochville, Transvaal, 1965.

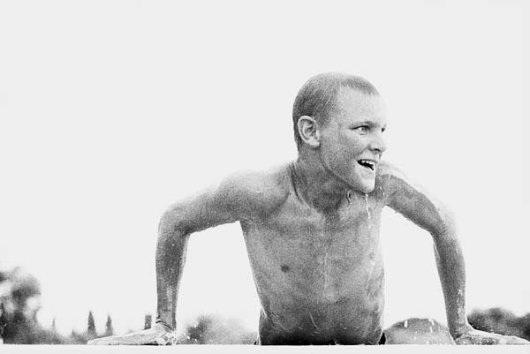

A young boy swimming, Aberdeen, Cape Province, 1966.

Policeman in a squad car on Church Square, Pretoria, Transvaal, 1967.

Kleinbaas with klonkie, Bootha Plots, Randfontein, Transvaal, January 1963.

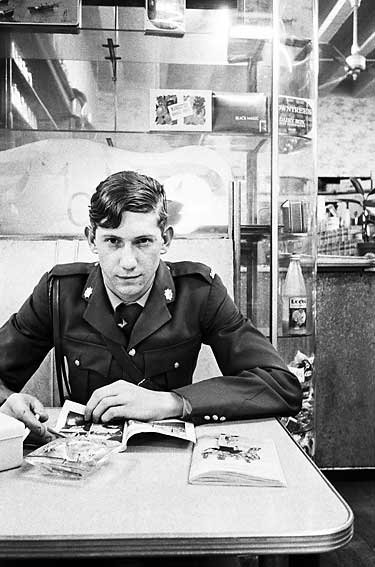

Young policeman in a café, Pretoria, Transvaal, 1967.

Source: Michael Stevenson

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

People seem afraid to comment on this post. I wonder why?

I wonder too what has happened to all these fine people, lucky to have lived in a saner world, not so lucky if, as I assume is true of at least some of the younger ones, they have lived to witness the present state of their fair nation.

Why don’t you tell us a little bit about what you are doing in South Africa?

Well most of us seeing these postings wonder why Mr. Cusack has gone to South Africa and what he is doing there. Since Mr. Cusack won’t tell us, that certainly puts a damper on questions or comments.

Given the photos posted here and Mr. Cusack’s well known political views one can speculate, but that’s hardly fair or often accurate. Given all that, perhaps from a distance a discrete silence is best.

And we think we have it tough in the U.S. Wow, it’s amazing how these people stick it out considering what has happened in their country in the last couple of decades, thanks largely to the democracies of the West. I feel so sorry for them.

I am merely a student and a traveller here.

I was much troubled by the contradictory feelings of liking, revulsion, and fear that these Afrikaner encounters aroused in me and felt the need somehow to come closer to these lives and to probe their meaning for me.

…

The man turns and says to the child, ‘Ja, wat maak jy hier, jou swart vuilgoed?‘ (Yes, what are you doing here, you black rubbish?), the insult meant and yet said with affection. How is this possible?

I would wager that such a thing is possible because the man was a man and not an angel. He does not choose once and forever set himself in heaven or hell. Rather, he constantly chooses, sometimes choosing good, other times choosing evil. Thus he is not some Platonic form of vice, but a mixture of virtuous and vicious habits that sometimes urge him one way, sometimes another. He is more than capable of being a mixture of wisdom, ignorance, fear, mistrust, wrath, affection, charity &c. all at once. In short, he is human. That such a thing should be surprising is… surprising.

I have a number of friends who have my back through thick and thin. They are like brothers to me, and have stood by me through any number of hardships. They can also be heretics and cads. I quite often dislike them because of this. But I love them always because of their virtues, however small those virtues might seem to others. I am sure most people could remember a friend, relation or acquaintance who they have similar feelings towards. If such people can be a mixture of the noble and the base, and if we see in ourselves a mixture of dislike and affection, then why would it surprise us that others are capable of the same mixtures?

Only the grace of God can fix all that is broken in man. When witnessing such an event we should pray that God erase the spite while preserving the affection. And we should also pray God that we are no worse than our closest friends believe us to be. May we be so blessed and lucky.

My apologies to Mr. Cusack if my rambling here is less than coherent.

Ever since I learned about the Afrikaners in my history classes at Penn, I have felt like I found a kindred folk (or in this case ‘volk’). Their history somewhat parallels that of the Spanish Americans in the Southwestern states–Californios, Nuevomejicanos, Tejanos, &c.–albeit with a much brighter prospect for the preservation of Afrikaner culture. A tribe mentality, while often entailing a superiority complex, often saves a minority culture from imminent death.

Where you dig this stuff up, I don’t know. But I do like it. Quaint, and very charming.

Being an Afrikaner myself and used to live in SA for all of my life, I can say that this is quite narrow-thinking about the Afrikaners, thinking that they all were “racists”! Shame…that people have that view, that shows that they haven’t travelled that much and haven’t met all of the Afrikaners and they don’t know about the many good deeds many did towards black people – or any other group. The same experience this “author” had… I’ve seen/experienced in the UK. Racism was and still is all over the world. Have you been to SA lately? Are you still there? What is happening in our country? It would be interesting to know what you exactly know – and can blog about – how things are deteriorating in every aspect of our society.

When I read the source and about the author, it all made sense why he wrote in such a negative tone. Afrikaans is not a “harsh” language, nor the people. Living in London for almost 7 years, I got to know more “harsh” people than I’ve ever met in my whole life and I’ve experienced more racism in the UK than ever in South Africa.

There are not many reasons for the ignorance of some Afrikaners, they were brainwashed to and in believing that they were God’s chosen people in South Africa, and rightfully the land belonged to them,but that is a load of crap. The ones behind all this fallacies are the educated ones, the predikante of the DRC, now these predikante due to their strong believe in God read the Bible and literally took for granted what they interpreted,as what their God wants of them,but the real culprits were the intelletuals that belonged to the Broederbond, who as a matter of fact domineered the Dutch Reformed churches of which there were two different branches, so began the political opinions of the Afrikaner political parties, which in turn produced such leaders, that introduced such evil policies of Apartheid and the one of note was Hendrik Verwoerd, who finally brought introduced his evil policies of seperate developement, that eventually destroyed minority white rule in South Africa, and the results can now be seen throughout the whole of South Africa, the poor whites are now suffering the consequences of their believes that was a fallacy from the beginning, that they were superior to the black people, who are now no better off then before the coming of the white man and colonisation

It is very easy to have an ambivalent attitude to this country & its peoples,not just the Afrikaners.

I myself find it difficult to reconcile the indescribable savagery of attacks on farms and homes with that of the general friendliness found at street level between the different population groups. It is quite true that amongst Afrikaners there is this affection and simultaneous reserve towards black people.Maybe less so in urban areas than on the platteland. After all the pressured urban human is internationally speaking a very differently socialized animal.

However, our South African society is still so frail that recent events such as the bloody slaying of a prominent far right figure,although he was not the most popular kid on the block(even in Afrikaner circles) has caused a deep sense of alarm in this community whose language, schools, universities, prospects and personal safety seem to be of no value at all to the present government.A virtual mental stage of siege is present amongst the farmers who have had up to 3000 of their members slaughtered since the new government took power in 1994 and the Commando system was made illegal and disbanded.

This country could only lose by continuing to exclude a historical minority who have contributed so much, often with their blood,(Google Anglo Boer war and the gold barons which directly lead to the emergence of Afrikaner nationalism), by a defeated impoverished and humiliated people, who incidentally were not compensated for damages incurred nor till today have received an apology from Britain for the various felonies committed by her.Indeed a butterfly affect in major.

I pray each night that our troubles are merely growing pains and that we will come right one day as I cannot see myself leaving South Africa nor deny my unborn children the priviledge of living in this beautiful country.

I believe we can but it will take swallowing some pride, learning to accept each other’s different values and an end to hate born of fear and misunderstanding both ways.

Miskien sal jy en jou gesin nog eendag kan terugkom huis toe, Nikita, na ‘n lewe sonder vrees. Ten opsigte van hoe dit nou hier gaan; dis moeilik om so oor die alles so oor die hoof te kam, maar laat ons se daar is mooi dinge en daar is lelike dinge aan die gebeur en ‘n mens kan maar net jou deel probeer doen, glo en vertrou.

i grew up in nietverdiend, as a white “kleinmiesies”.

my father who also grew up in nietverdiend on the farm Heimweeberg, yes it’s either him or my uncle in the photo, thaugt me the importance of forgiveness and respect.

the past will never be the past if we don’t let it go.

easy for me to say, maybe, but i have seen what hate can do.

we need to respect each other and understand that he or she may not be ready to forgive and forget. if we bulldoze someone into “forgiving” us they will not do that.

thank you for your research!

Annarie