About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Dahlgren Residence

No. 15 East Ninety-Sixth Street, New York

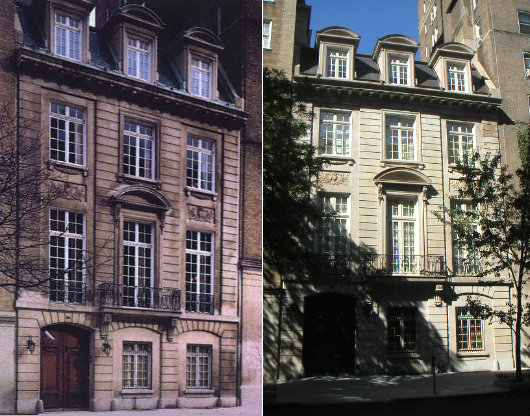

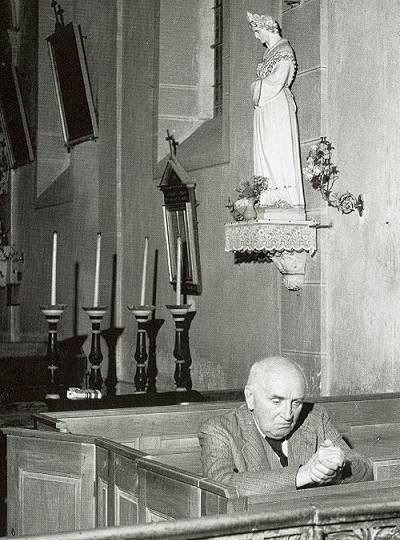

THE UPPER EAST SIDE is crossed by a number of wider cross-streets, of which 96th Street has long been agreed as the northern boundary of the neighborhood. (Overeager real estate agents have recently taken to advertising properties above that boundary as being located in the “Upper Upper East Side”). At number 15 on East 96th Street sits a splendid townhouse of superb design and execution often known as the Dahlgren residence. (Seen above, before and after complete restoration).

Lucy Wharton Drexel was of the Philadelphia Drexels, from which also came Saint Katharine Drexel, the founder of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, as well as the initiators of Drexel University in that Pennsylvanian city. Young Miss Drexel married Mr. Eric B. Dahlgren, son of Admiral John A. Dahlgren, inventor of the Dahlgren Gun used during the Civil War at a ceremony in the Philadelphia cathedral officiated by Archbishop Corrigan of that see, and the couple soon moved to Manhattan where Mr. Dahlgren had a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. The Dahlgrens themselves were a prominent Catholic family, with Eric and his brothers attending Georgetown University, where to this day the main chapel bears the Dahlgren name. (Well-to-do Catholics must have been in short supply at the time, because after Lucy and Eric’s marriage, Lucy’s sister Elizabeth was married to Eric’s brother John).

Un petit peu de Paris dans le meilleur arrondissement de New York.

The Dahlgrens (Eric & Lucy, that is) raised eight children at their house at 812 Madison Avenue as well their country house in Lawrence, L.I., but despite the bountiful progeny, the marriage was not a happy one. Only two months after Lucy’s devoutly Catholic mother died, Mrs. Dahlgren initiated a suit for divorce from her husband in March 1912, citing his infidelity. Escaping to Europe with the children for the duration of the proceedings, she returned to New York in 1915 after the divorce was settled and purchased the 38′ x 100′ plot at 15 East 96th Street.

Lucy chose the renowned architect and designer Ogden Codman Jr., who had written the influencial Decoration of Houses alongside Edith Wharton, to design a beaux-arts townhouse in the wide Parisian style. Codman himself had built his own beaux-arts townhouse a few doors down at No. 7 East 96th Street, and the architect hoped that the wide thoroughfare could be developed as an elegant Parisian residential boulevard.

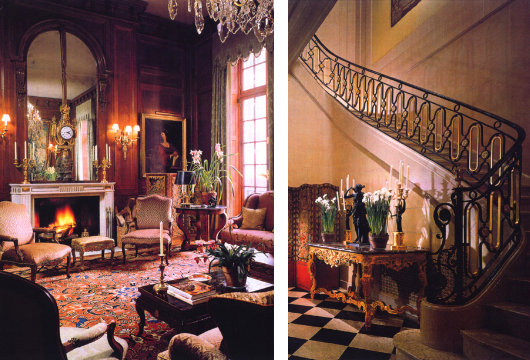

For the Dahlgren residence, he created a building with thirty rooms, eleven bathrooms, seven fireplaces, a grand marble staircase, an octagonal dining room, and a ground-floor carriageway that went through the house to an auto turntable at the back. Lucy Dahlgren, however, did not spend a great deal of time in the elegant edifice, and she leased the house out from 1921, and later selling it in 1927. She died in 1944, aged seventy-seven years, in Newport, Rhode Island.

The man she leased and finally sold No. 15 to was Pierre C. Cartier, the founder of the eponymous jewelry firm, who moved into the townhouse with his wife and children. The Cartiers were great hosts and held dinners for many French dignitaries, artists, and intellectuals, especially during the Second World War when many of the aforementioned chose New York as their place of exile.

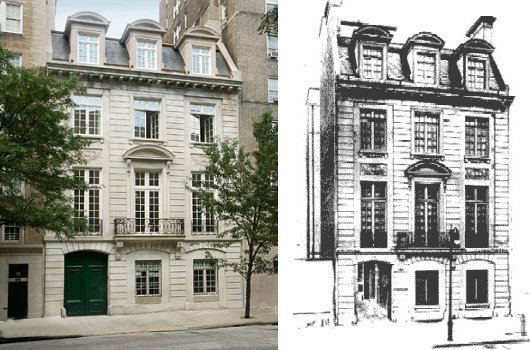

Paul Claudel: poet, playwright, diplomat.

One of the most prominent of their frequent guests was the celebrated poet and playwright Paul Claudel during his tenure as the Ambassador of the French Republic to the United States from 1928 to 1933. Claudel, whose elder sister was the sculptress Camille Claudel, had been a diffident, conflicted young man until the night of Christmas Eve, 1886. It was that night that he drifted into the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris and heard vespers being sung, and began his return to the Church. Coincidentally (if we dare call it coincidence), that very same evening of Christmas Eve, 1886, the young Thérèse Martin — St. Thérèse of Lisieux — experience a conversion of her own, later writing in her spiritual biography that “On that luminous night, Our Lord accomplished in an instant the work I had not been able to do during years”.

While the Dahlgrens could not find enduring love at No. 15, the home was more than a blessing to the Cartiers… and the Claudels. In 1933, Marion Rumsey Cartier, Pierre & Elma Cartier’s daughter, and Pierre Claudel, Paul & Sainte-Marie Claudel’s eldest son, were joined in holy matrimony. In 1946, Paul Claudel was named to the Académie française (where the seats of the ostracized Marèchal Pétain and Charles Maurras were left empty out of respect until their deaths in 1951 and 1952, respectively). The following year, the Cartiers shifted to their house on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland, where Mrs. Cartier died in 1959, and Pierre following her in 1964.

With Pierre Cartier’s death, No. 15 was sold to the Convent of St. Francis de Sales, who remained there for seventeen years. In 1981, the Convent sold the house to financier Barry Trupin (arrested, in 1997, for the honorable crime of tax evasion) for $3,000,000, who in turn sold it to businessman Paul Singer in 1987 for $5,700,000. Under Singer’s watchful eye, the building was carefully restored from the ground up, and used to display his large collection of porcelain vases. (The following three photographs are from the Singer restoration). No. 15 is currently valued at over $17,000,000.

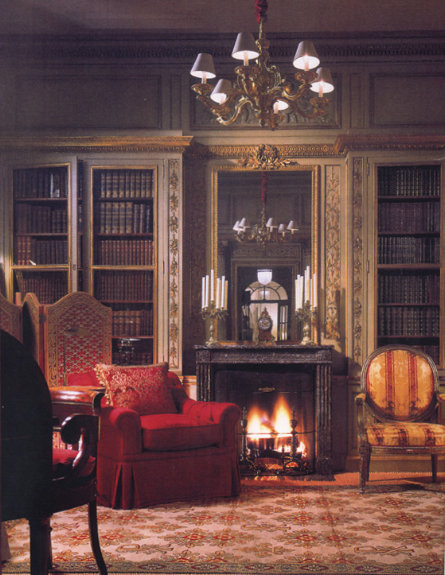

The library.

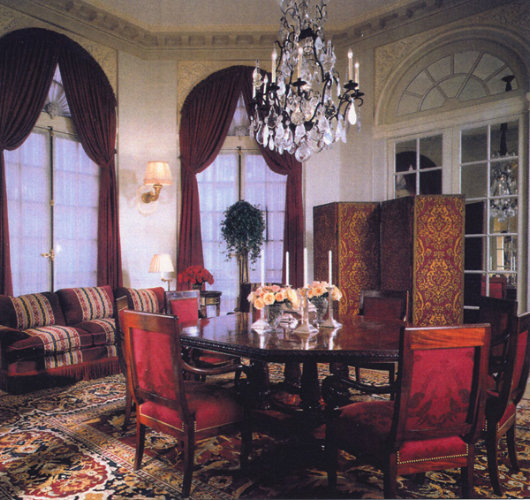

The octagonal dining room.

Speaking, as we were, of Christmas Eve, Ogden Codman’s residence down the block at No. 7 was sold by Codman to Edith Moore, the daughter of Joseph Pulitzer, and her husband William S. Moore, great-great-grandson to Clement Clarke Moore, purported author of the Christmas classic A Visit from St. Nicholas (“Twas the night before Christmas, and all through the house…”). The Moores sold it on in 1948, and donated the books Codman has left in the house to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1965, No. 7 became home to the Manhattan Country School, which continues to use the Codman residence as its seat to this present day. Codman’s dream of a Parisian residential boulevard in New York was not to be, as the remaining properties on the block were developed as apartment buildings in the 1920s. The only other townhouse on the block is the more narrow No. 12, which today serves as La Scuola d’Italia “Guglielmo Marconi”, Italy’s answer to the Lycée Français de New York.

Previously: The Neue Galerie | The Goodwin Mansion | The Goodwin Mansion II

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Lovely post, Andrew.

What a pleasure it would be to have you as a guide to New York!

Ah, you mention St. Therese, the Little Flower of Jesus. Just a few nights ago, I watched Alain Cavalier’s masterfully understated & deeply moving 1986 film, “Therese.” Have you ever seen it?

Andrew, I greatly enjoy and appreciate your posts on architecture. I look forward to the next one!

A quibble: you write that Barry Trupin was arrested for “the honorable crime of tax evasion.” Tax evasion is not honorable in the least. As is typical for high-dollar tax cheats, Trupin specialized in elaborate deception.

The Second Circuit recently found:

“The tax fraud occurred over six years and accounted for over six million dollars in unreported income. Trupin accomplished his tax evasion through a complex network of corporate shells, phony paper trails, and foreign transactions – efforts that required him to take advantage of his wife and daughter. . . . Trupin in effect stole from his fellow taxpayers by his deception.”

I urge you to reconsider your off-the-cuff remark that tax evasion is an honorable crime. (Especially in the case of a man whom Forbes has described as “a crooked parvenu with bad taste.”)

I still maintain that tax evasion is an honorable crime, though I certainly concede that it appears Mr. Trupin’s particulars make his a dishonorable example thereof.

In this country, really, you’re just better off paying your taxes. The risk isn’t worth it, unless of course you’re a friend of the Clintons, in which case you just flea the country until your pardon is announced on his/her last day in office.

I like the image–the Clintons and Marc Rich did indeed flea the country!

In light of the Lord’s injunction that we render to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and St. Paul’s instruction to obey the laws of the state in Romans 13, how can tax evasion be honorable? Is your position that tax evasion can be both sinful and honorable?

To approach the question another way, tax evasion is, as the Second Circuit put it, stealing from your fellow taxpayers. How can that be honorable?

Ah, but are we morally bound to pay taxes that fund unjust wars, the de-Christianization of foreign countries, and third-world abortions? And if we do pay those taxes, does that make us moral agents in those acts?

Are the Italians all sinful for skimping on their taxes, or does the fact that tax evasion in Italy is part of the national culture excuse them? Surely we cannot accept the concept that just because everyone’s doing it makes it alright?

There are many interesting questions, but I have merely to offer the suggestion that passing jocular comments not be taken as weighted declarations. One mustn’t take things so seriously. This is a frivolous website, not the Summa theologica…

My apologies for excessive seriousness. I’m a tax lawyer (with a law firm, I hasten to add, not with the IRS), which makes me very sensitive to issues of tax fraud.

I will let the passing jocular comment drop, with only one further comment.

Your first paragraph above is the classic move; I’ll offer the classic response. The blasphemous Roman government under Caesar was certainly not less moral than the current US government. Yet the command was to render taxes to it.

Correction: “certainly not more moral.”

Thanks for the glimpse of one of Manhattan’s architectural jewels, Andrew. You also answered a question for me about the origins of Dahlgren Chapel at Georgetown University.

You should visit Washington some time (I recommend October) and stroll about some of the neighborhoods in “Northwest”–e.g., Kalorama and Embassy Row. You’ll find some lovely old buildings there.

Hi Andrew,

What an interesting piece and photos. As a parent at Manhattan Country School I have always wondered about the insides of Number 15.

If you would be interested in visiting MCS in the fall, they always enjoy showing the building to people interested in architecture. They also have a wonderful set of photographs of the construction of the building that show how 96th St. looked at the time. Please feel free to call or email them (or me).

ScurvyOaks,

Could one not argue that there is a limit to the state’s natural right to levy taxes? Surely if Caesar demands 90% of one’s income (pardon the hyperbole) he should be resisted.

An excellent post. I especially liked tidbit about Paul Claudel. By the way I detect a certain failure of the Singer restoration to internalize the supreme quality and character of the beaux-arts facade. For one thing, the colors of the furniture and carpets are too various and somber.

Dino, I tend to agree that there is some limit to the state’s natural right to levy taxes. From the standpoint of the limit on the Christian’s obligation to obey the laws of the state, I’d construct the argument like this:

A Christian should (indeed, must) disobey human laws that command what God forbids or forbid what God commands. God’s law requires a Christian to support the Church financially. (I’m deliberately avoiding an argument over whether the tithe is required.) Scripture also says that anyone who does not provide for his family has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever. 1 Tim. 5:8. In light of these two commands, there is seemingly some level at which excessive taxation can rightly be resisted.

But, because “render unto Caesar” does not carry an explicit exception, and God’s word should always be interpreted based on the principle that it is internally consistent in its moral imperatives, I think it takes pretty extreme taxation for the argument above to carry much weight. Just by way of historical background, the top US individual marginal income tax rate has been as high as 91% — that’s not a typo, it really was 91% — but that was only on very high incomes, and it was at a point where federal income tax law had a lot of genuine loopholes, which everyone understood were present in the law and were legitimate ways to reduce tax liability.

ScurvyOaks, I agree that if taxation made it extraordinarily difficult to support one’s family or the Church, that the latter two should take precedence. However, those are not the only reasons for resisting high taxation. The principal reason, IMHO, is that the state’s natural right to tax has natural limits (regardless of one’s ability to pay). If the state exceeds those limits, one’s obligation to pay reduces proportionately. Just taxes have to be ordered to the common good. If tax rates are extortionate, then they are unjust, and an unjust law is no law at all.

Even when there is moral culpability, tax evasion seems to be a mere venial sin, from what I can tell, unless the amount being effectively stolen from the common good is large.

Michael F., please email me, I don’t have your email address.

Old Dominion Tory:

Are you aware that some of the building in Kalorama were trasported from Europe? Quite amazing.

Dino, I respectfully and heartily disagree with the proposition that “an unjust law is no law at all.” IMHO, there is a great deal of moral difference between working to change an unjust law and disobeying it. This is true in any political context; it is true with particular force in a polity in which laws are made by elected representatives.

The notion that “an unjust law is no law at all” is an invitation to anarchy. Do you really want everyone to obey only the laws that he considers just?

More importantly, it’s worthwhile to revisit Romans 13:1-7:

1Everyone must submit himself to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God. 2Consequently, he who rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and those who do so will bring judgment on themselves. 3For rulers hold no terror for those who do right, but for those who do wrong. Do you want to be free from fear of the one in authority? Then do what is right and he will commend you. 4For he is God’s servant to do you good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword for nothing. He is God’s servant, an agent of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer. 5Therefore, it is necessary to submit to the authorities, not only because of possible punishment but also because of conscience. 6This is also why you pay taxes, for the authorities are God’s servants, who give their full time to governing. 7Give everyone what you owe him: If you owe taxes, pay taxes; if revenue, then revenue; if respect, then respect; if honor, then honor. (NIV)

Not a particularly pleasant set of instructions to obey, especially in situations in which there is much that the governing authorities do that is morally questionable (to put it mildly). But there it is.

ScurvyOaks,

The principle “an unjust law is no law at all” comes from St. Augustine, and has pretty much been adopted as Church teaching through the ages, from what I can tell. So you’ve got some tough sledding ahead if you’re going to argue that.

You make a good point about anarchy. St. Thomas provides an extremely balanced view (of course) in the Prima Secundae of the Summa Theologica, particularly question 96, article 6:

“As stated above (4), every law is directed to the common weal of men, and derives the force and nature of law accordingly. Hence the jurist says [Pandect. Justin. lib. i, ff., tit. 3, De Leg. et Senat.]: “By no reason of law, or favor of equity, is it allowable for us to interpret harshly, and render burdensome, those useful measures which have been enacted for the welfare of man.” Now it happens often that the observance of some point of law conduces to the common weal in the majority of instances, and yet, in some cases, is very hurtful. Since then the lawgiver cannot have in view every single case, he shapes the law according to what happens most frequently, by directing his attention to the common good. Wherefore if a case arise wherein the observance of that law would be hurtful to the general welfare, it should not be observed. For instance, suppose that in a besieged city it be an established law that the gates of the city are to be kept closed, this is good for public welfare as a general rule: but, it were to happen that the enemy are in pursuit of certain citizens, who are defenders of the city, it would be a great loss to the city, if the gates were not opened to them: and so in that case the gates ought to be opened, contrary to the letter of the law, in order to maintain the common weal, which the lawgiver had in view.

Nevertheless it must be noted, that if the observance of the law according to the letter does not involve any sudden risk needing instant remedy, it is not competent for everyone to expound what is useful and what is not useful to the state: those alone can do this who are in authority, and who, on account of such like cases, have the power to dispense from the laws. If, however, the peril be so sudden as not to allow of the delay involved by referring the matter to authority, the mere necessity brings with it a dispensation, since necessity knows no law.”

http://snipurl.com/1p0o8

So I suppose I would have to argue that the key to the tax evasion question is the bit about “instant remedy” and “necessity” in the second paragraph. If one’s taxes are burdensome, clearly one cannot wait for an appeal to the competent authorities, and one would not commit any sin in evading taxes. However, in cases where the taxes are not burdensome, yet are nevertheless unjust, one ought to make a case to the authorities.

I don’t see anything there that contradicts St. Paul.

My apologies for letting this lapse for so long. Also, I hope our gracious host is not becoming bored by this back and forth on his bandwidth. Please let me know, Cusack, if you would like this dialogue to proceed off-line, as I would happily provide my email address to Dino.

Dino, this is the point where I need to advise you of the scandalous reality that I am a Protestant. :) So when you explain that “The principle ‘an unjust law is no law at all’ comes from St. Augustine, and has pretty much been adopted as Church teaching through the ages,” this does not convey the same aura of authority to me that it would to a Roman Catholic. Both as an adherent to the Reformed tradition and as someone with a sincere affection for the Roman Catholic Church, I am eager to learn about and learn from Rome’s positions, which I almost always find to be well thought-through (even when I disagree with them, as a function of different premises).

All that said, “an unjust law is no law at all” strikes me as the sort of ringing slogan that sounds great until you try to put it into practice. It proves too much; it proves more than St. Thomas advocates.

Now on to St. Thomas’s careful analysis. I agree completely with what you have quoted from the Summa. I do not draw the same conclusions from it that you do, however.

I think it’s important to draw a clear distinction between what St. Thomas says to the administrator of the law and what he says to the citizen. To the adminsistrator: “By no reason of law, or favor of equity, is it allowable for us to interpret harshly, and render burdensome, those useful measures which have been enacted for the welfare of man.” By contrast, to the citizen: “if the observance of the law according to the letter does not involve any sudden risk needing instant remedy, it is not competent for everyone to expound what is useful and what is not useful to the state: those alone can do this who are in authority, and who, on account of such like cases, have the power to dispense from the laws. If, however, the peril be so sudden as not to allow of the delay involved by referring the matter to authority, the mere necessity brings with it a dispensation, since necessity knows no law.”

It is extremely rare that paying one’s taxes involves a peril so sudden as not allow of the delay involved by referring the matter to authority. This is especially so under US federal income tax law, which permits any taxpayer to file with the IRS a claim for refund within 3 years after paying his taxes and, if this claim for refund is denied by the IRS, to puruse such claim in federal district court.

My particular quibble is with the idea that “burdensome” is the right standard for a taxpayer who decides not to pay what the law demands. I’ve dealt with a lot of taxpayers during my 20 years of law practice, and a very substantial percentage of them have thought their taxes “burdensome.” To return to St. Thomas, “burdernsome” is what the administrator should avoid in applying the law; it is not the standard that the Doctor offers to those charged with observing the law. Given especially our fallen tendency toward greed, to offer dispensation for anyone who does not pay his taxes because he believes them burdensome is to open the door very wide indeed — wider than either St. Paul or St. Thomas would advocate, if I have understood them correctly.

Hello,

I have a hand written poem by Louis Dantin. I am sure it is the original draft because there are many changes where he has drawn a line through parts of it and rewrote a word or line. You can still read his original thoughts. There are several titles to this original draft of La Femme Ideale.

There is another original poem titled Stance Paienne typed and signed by Louis Dantin.

I found these poems in the personal folder of Leon Loranger I acquired from an estate sale.

This manuscript has information about Paul Claudel’s reception and influence in North America written by father Leon Loranger OMI. (I think part of it is the class he taught at Universite Laval en juillet 1939) One of Loranger’s many achievements is a title conferred on him by the government of France Knight of the Legion of Honor. He lectured at many universities and churches on this subject. The manuscript is around 150 pages long written in French. I have biography information on Leon Loranger obtained from the Vatican by Douglas Speakhart archivist OMI Washington D.C.

It is a leather folder with the initials L.L. (Leon Loranger) on the cover. On the inside is says A Mon Cher AMI Leon (underneath) Albert Florence 30 Juin 1932.

The first folder shows the growth and development of St. Jean Baptiste Province of Lowell. OMI (Oblat of Mary Immaculate) of St. Peter’s parish in Plattsburgh, St. Joeph’s and Notre Dame de Lourdes in Lowell and parishes in Aurroru, Egg Harbor and Fond-du-Lac, Wisconsin over 2 million Catholics. Leon Loranger was director from 1934-1946.

It is titled:

Les Franco-Americains En Nouvelle-Angleterre

au point de vue catholique

Etude de statistique

~ 38 pages long.

The second folder is titled:

III

Les Realisations

C

Le Soulier de Satin

I

~ 15 pages long.

The third folder is titled:

III

Les Realisations

C

Le Soulier de Satin

II

~ 10 pages long.

The fourth folder is titled:

III

Les Realisations

B

Les Poesies

~ 16 pages long.

The fifth folder is titled:

Leon Loranger,O.M.I.

Paul Claudel

1;Homme et 1;Oeuvre.

Cours professe

a 1;Universite Laval

en juillet 1939

~ 24pages long.

The sixth folder is titled:

III

Les Realisations

A

Le Theatre

~ 20 pages long,

The seventh folder is titled:

II

L; Art Poetique

~ 22 pages long.

Best regards,

Steven Simmons

This house used to belong to my family and grandfather, paul singer, I remember being there as a kid and thinking it was the most amazing place, which it is.